Glenn Engstrand

Software architects and developers often need to understand the structure and complexity of codebases, whether it’s for onboarding, planning refactoring, or simply assessing maintainability. Static code analysis provides a powerful lens, offering quantitative insights without running the code.

I recently released a free-to-use web app where you can ask software architecture questions about eight popular open-source services. The answers come from an artificially intelligent large language model using a prompting technique called retrieval augmented generation. I performed static code analysis on the underlying source code repositories to accomplish this. The data informing this blog comes from that analysis.

In this post, we’ll explore static code analysis metrics for the following eight prominent open-source projects:

Apache Cassandra is an open-source NoSQL distributed database trusted by thousands of companies for its scalability and high availability without compromising performance. Its linear scalability and proven fault tolerance on commodity hardware or cloud infrastructure make it the perfect platform for mission-critical data.

Debezium is a set of distributed services that capture changes in your databases. Your applications can consume and respond to those changes. Debezium captures each row-level change in each database table in a change event record and streams these records to Kafka topics. Applications read these streams, which provide the change event records in the same order they were generated.

Apache Druid is a real-time analytics database for fast slice-and-dice analytics (“OLAP” queries) on large data sets. It often powers use cases where real-time ingestion, fast query performance, and high uptime are essential.

Elasticsearch is an open-source distributed, RESTful search and analytics engine, scalable data store, and vector database capable of addressing many use cases. As the heart of the Elastic Stack, it centrally stores your data for lightning-fast search, fine‑tuned relevancy, and powerful analytics that scale easily.

Apache Kafka is an open-source distributed event streaming platform many companies use for high-performance data pipelines, streaming analytics, data integration, and mission-critical applications.

Apache Lucene™ is a high-performance, full-featured search engine library written entirely in Java. It is a technology suitable for nearly any application requiring structured, full-text, faceting, nearest-neighbor search across high-dimensionality vectors, spell correction, or query suggestions.

A Neo4j graph database stores data as nodes, relationships, and properties instead of in tables or documents, so you can similarly organize your data when sketching ideas on a whiteboard. Since graph databases are not restricted to a pre-defined model, you can use more flexible approaches and strategies when working with them.

Apache Spark™ is a multi-language engine executing data engineering, data science, and machine learning on single-node machines or clusters.

Why did I pick these open-source projects and not other popular open-source projects? Mostly because I like them. I’ve used them multiple times. They are well designed, anti-fragile, and they scale easily. I have wondered on occasion what it would take to make some enhancement to them. That is why I released the Ask the Architect app.

The goal here isn’t to declare winners or losers but to use metrics to understand these systems’ shape, scale, and potential complexity hotspots.

Metrics Overview

I’ll focus on key metrics at the repository (repo) and package levels.

Number of Files: A basic measure of project size. I count only code files, not documentation, configuration, or build files.

Lines of Code (LoC): This is another size measure often looked at per file (using the median here to resist outlier influence). These counts are only on code files and do include comments.

Cyclomatic Complexity: Originally developed by Thomas McCabe in 1976, this metric measures the number of linearly independent paths through a piece of code. Higher values often indicate more complex logic that can be harder to test and maintain. We’ll look at the mean per file for the repo and the standard deviation within specific packages.

Fan-In: At the package level, this counts how many other packages depend on (import classes from) a given package. High fan-in suggests a package is central, and changes could have wide-ranging impacts.

Repo-Level View: Size and Average Complexity

Let’s start with a bird’s-eye view of the repositories.

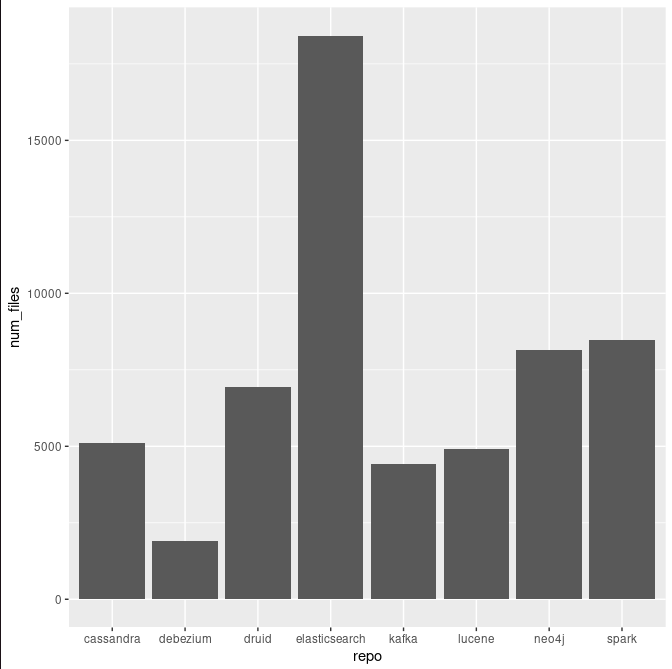

- Project Size (Number of Files)

Immediately, we see significant variation in scale. Elasticsearch is the largest project by file count, exceeding 18,000 files. Spark and Neo4j are also substantial. On the other end, Debezium has a much smaller footprint. Cassandra, Druid, Kafka, and Lucene fall somewhere in the middle. While Elasticsearch embeds Lucene at runtime and has some Lucene-specific packages, none of the Lucene code is in the Elasticsearch repo. All of the static code analyses here treat Lucene and Elasticsearch as separate.

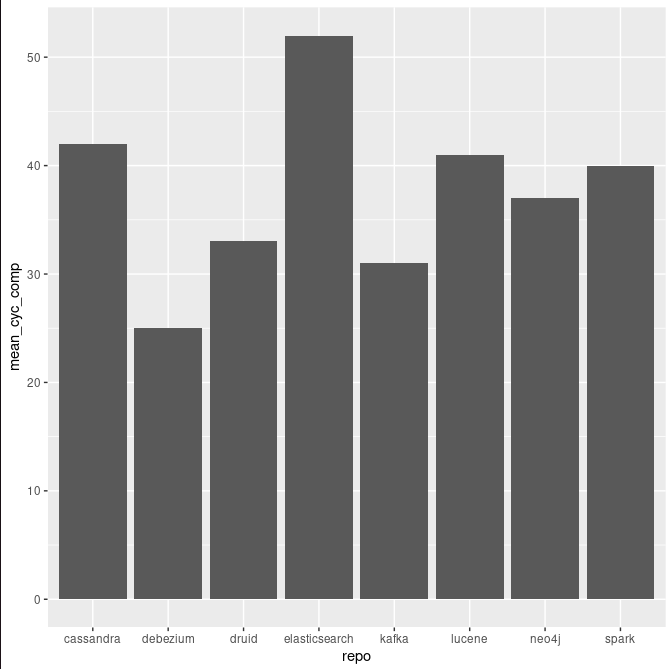

- Average File Complexity (Mean Cyclomatic Complexity)

While size is one thing, complexity is another. This chart shows the average cyclomatic complexity per file. Again, Elasticsearch leads, suggesting its average file contains more complex branching logic than the others. Cassandra, Lucene, Spark, and Neo4j also show relatively high average complexity. Debezium, consistent with its smaller size, shows the lowest average complexity per file.

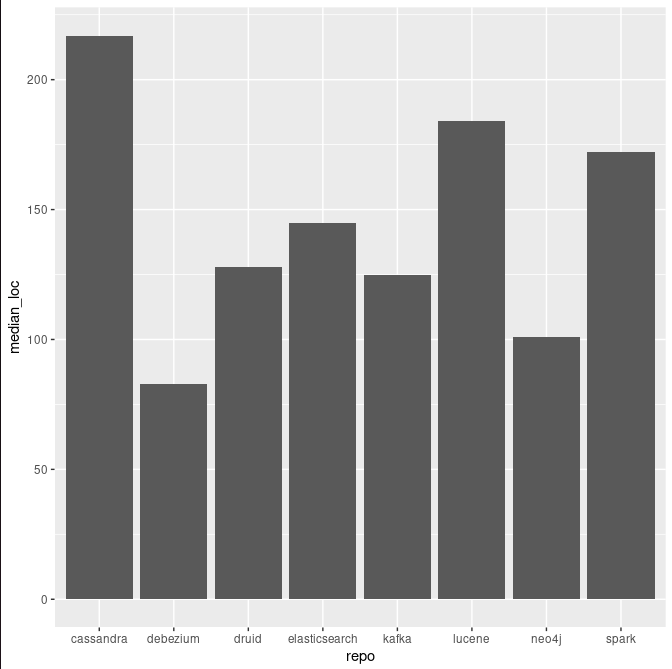

- Typical File Length (Median Lines of Code)

Median Lines of Code give a sense of a file’s typical length. Interestingly, Cassandra has the highest median LoC, indicating that half of its files are over ~220 lines long. More on this later. Lucene and Spark also tend to have longer files on average. Neo4j and Debezium have the lowest median LoC, suggesting smaller files might be their typical structure. Elasticsearch, despite its high file count and complexity, has a more moderate median file length than Cassandra.

Diving Deeper: Package-Level Hotspots

Averages can hide details. Complexity and size are rarely distributed evenly. Let’s examine specific packages identified as the most complex or extensive within these projects.

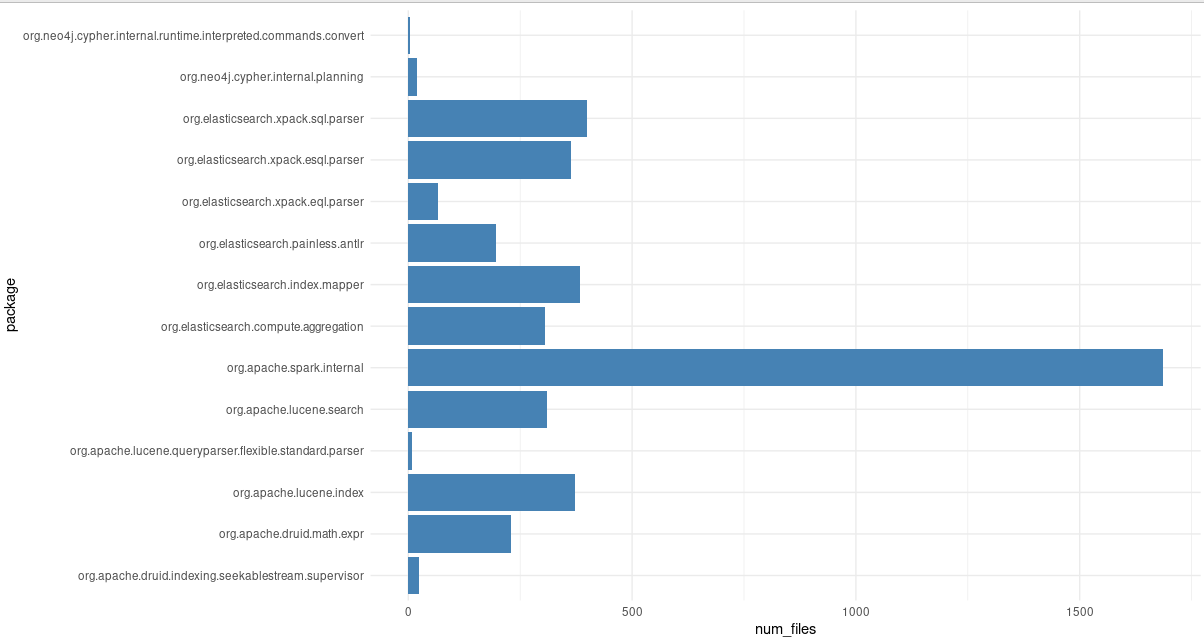

- Size Distribution (Number of Files in Key Packages)

This chart highlights specific packages with a large number of files. The org.apache.spark.internal package is massive, containing over 1500 files. Several Elasticsearch packages (like xpack.sql.parser, index.mapper, compute.aggregation) and Lucene packages (search, index) are also extensive, indicating significant functionality is concentrated within them.

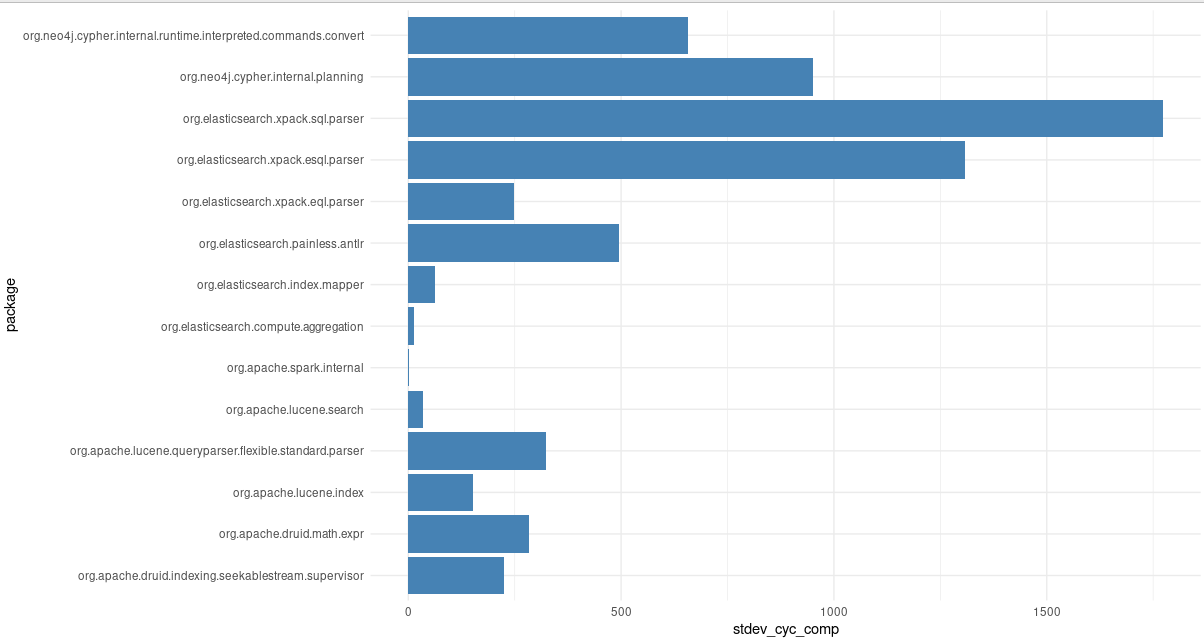

- Complexity Variation (Standard Deviation of Cyclomatic Complexity)

Standard deviation tells us about the spread of complexity within a package. A high value means a package contains a mix of simple and very complex files. Elasticsearch’s xpack.sql.parser and xpack.esql.parser shows extremely high standard deviations. This deviation suggests that while the package handles SQL parsing, its complexity varies dramatically between its components. Neo4j’s cypher.internal.planning also shows significant variation.

In contrast, packages like org.elasticsearch.index.mapper have lower variation despite potentially high average complexity (not shown here), suggesting more uniform complexity across its files. Why not show average cyclomatic complexity? I could have done that instead. That graph looks very similar and identifies the same packages.

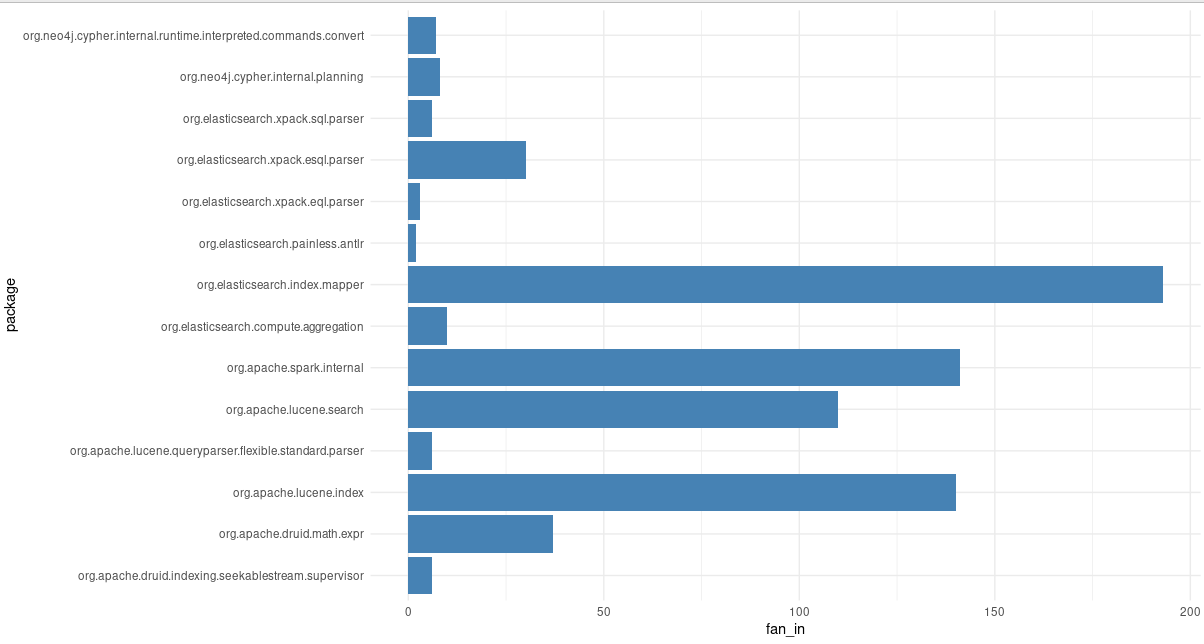

- Inter-Package Dependencies (Fan-In)

Fan-in highlights how central a package is. Elasticsearch’s index.mapper package has the highest fan-in among this selection, with nearly 200 other packages depending on it. This high fan-in makes sense – mapping is core to a search engine. Similarly, Spark’s internal and Lucene’s index packages show high fan-in, indicating their centrality within their respective systems. Changes in these high fan-in packages require careful consideration due to their potential impact.

Cassandra LoC Revisited

Earlier in this blog, we covered that Cassandra had the largest median LoC. Why would Cassandra have such large code files? That is hard to say. Here is a short list of some of the most oversized packages.

| package | median_loc | mean_loc |

|---|---|---|

| org.apache.cassandra.cql3.functions.types | 3173 | 1886 |

| org.apache.cassandra.index.sasi.utils.trie | 1152 | 936 |

| org.apache.cassandra.index | 1066 | 897 |

| org.apache.cassandra.db.filter | 989 | 759 |

| org.apache.cassandra.db.context | 915 | 915 |

| org.apache.cassandra.utils.bytecomparable | 857 | 791 |

| org.apache.cassandra.utils.btree | 695 | 2196 |

| org.apache.cassandra.index.sasi.disk | 673 | 567 |

| org.apache.cassandra.service.paxos | 652 | 673 |

| org.apache.cassandra.io.sstable.format.big | 651 | 549 |

After reviewing the code, I see that they tend to group things like the schema data types or codecs into a single file. They employ a variation of the singleton pattern where multiple implementations of an interface are private static inner classes to that interface. Is that bad? Well, not really. It’s not great if multiple developers change different codecs in the same sprint. How often does that happen? Probably not often.

Caveats: Reading the Tea Leaves

It’s crucial to interpret these metrics with caution.

There is no single best metric. Code size or cyclomatic complexity alone doesn’t determine code quality. High complexity might be necessary for a complex domain.

Context Matters: It is difficult to compare a database (Cassandra) directly with a streaming platform (Kafka) or a search library (Lucene) based purely on these numbers. Their domains dictate different structures.

These are all “Healthy” open-source projects, meaning they are all successful, well designed, easily adopted, and widely used. The metrics reveal structure and potential areas of interest, not necessarily fundamental flaws. They represent different architectural choices and scales.

Limited View: This analysis only scratches the surface. It doesn’t cover aspects like code duplication, test coverage, dependency age, or specific code smells.

Conclusion: Diverse Landscapes

Our static analysis journey across these eight open-source projects reveals a diverse landscape.

Scale & Scope: Projects like Elasticsearch, Spark, and Lucene demonstrate massive scale, potentially acting as “kitchen sinks” covering broad functionality within their domains. Elasticsearch stands out for both its size and average per-file complexity.

Focused Footprints: Debezium presents a much smaller, more concentrated codebase with lower average complexity metrics.

Varied Structures: Cassandra tends towards longer files (high median LoC), while Neo4j leans towards shorter ones.

Identified Hotspots: Specific packages within Spark (internal), Elasticsearch (index.mapper, xpack.sql.parser), and Lucene (index, search) emerged as significant hubs of size, complexity variation, or high inter-dependency (fan-in).

Static code analysis doesn’t provide all the answers, but it offers invaluable quantitative insights into the structure and characteristics of software systems. We can better understand, navigate, and make informed decisions about even the largest and most complex codebases by looking at metrics like file count, complexity, LoC, and fan-in at different granularities.